1. Introduction

Note on Terms: Throughout this report, I use Kansei-based Well-being to capture the uniquely Japanese concept of kansei—a dual process of sensory perception (入力) and expressive output (表現). In English, I describe this as sensory‑expressive well‑being, emphasising that kansei encompasses both feeling and creative expression.

1.1 Social Context

Have you noticed that knitting has become a trend recently? Yarn is running out of stock in stores, reflecting its growing popularity. The quiet, focused time spent moving one’s hands and immersing oneself in knitting—a form of handwork—has gained widespread appeal, partly influenced by social media. It is enjoyed by people of all ages, from middle and high school students to homemakers and seniors.

This state of deep engagement in an activity is known as “flow,” which has been shown to enhance people’s sense of happiness and well-being (Csikszentmihalyi, 1990).

Moreover, artistic activities are said to promote mental health. They can boost self-esteem, reduce anxiety and stress, improve communication, and foster creativity (Clark, 2024).

The rising interest in handwork also reflects broader shifts in societal values across Japan. According to a Cabinet Office survey (2022), 48.9% of respondents said they take pride in Japan’s “excellent culture and arts,” while 45.5% expressed pride in the country’s “long history and traditions.” In addition, over half of the population (53.4%) responded that, having achieved a certain level of material wealth, they now wish to place greater emphasis on inner fulfilment and a more relaxed, meaningful life.

From this perspective, the growing interest in creative and traditional craftwork may be seen as an expression of cultural pride and a desire for a deeper, more internalised sense of happiness and contentment.

At the same time, the survey also highlighted that younger generations still tend to place strong emphasis on “material abundance.” This gap raises important questions about how handwork and sensory-based activities can resonate with young people and how they might contribute to their well-being in the future.

1.2. The Edo Kiriko Glass Studio “Hanashyo”

So, do Japanese artisans experience flow states or express creativity through their handwork? What other factors influence their well-being? In search of these insights, I turned my attention to Edo Kiriko, a traditional form of handicraft originating from the Edo period. I was fortunate to have the opportunity to speak with Mrs. Chisato Kumakura, Director of Hanashyo, a renowned Edo Kiriko studio located in Nihonbashi—one of the cultural centers of traditional Japan.

< What is Edo Kiriko? >

Before diving into the main topic, how much do you know about Edo Kiriko?

Edo Kiriko is a traditional Japanese craft that originated around 190 years ago in the late Edo period. It was first created by a glass craftsman named Kyubei Kagaya in Nihonbashi. This art form features delicate and intricate patterns engraved into colored glass, often representing motifs that symbolize Edo culture.

< Characteristics of “Hanashyo” >

Hanashyo is a globally recognised Kiriko brand that respects traditional Japanese aesthetics while embracing new techniques and designs. For example, unlike conventional crystal glass—which contains environmentally harmful lead—Hanashyo uses soda glass made from natural sand, ensuring a lower ecological footprint.

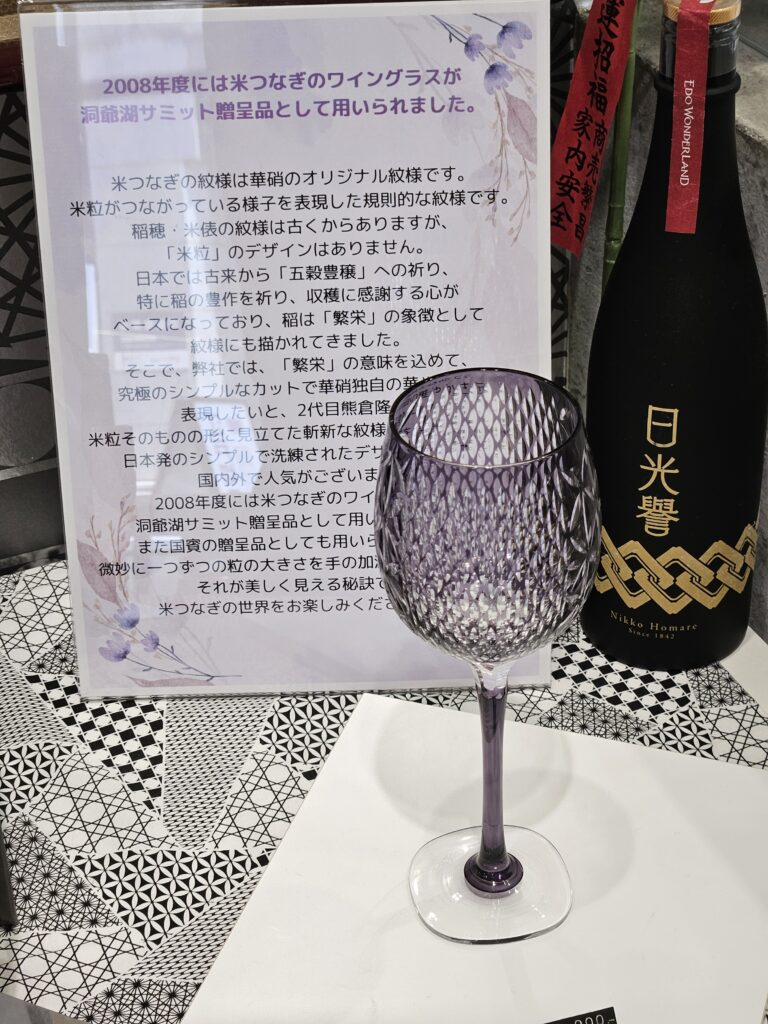

The studio’s timeless sensibility inspires curiosity, individuality, and emotional sensitivity in those who use their pieces. In addition to traditional cut patterns, Hanashyo has also developed its own unique motifs. One example is the “Kome-tsunagi” (linked rice grain) pattern, inspired by rice, a symbol of prosperity and the wish for a bountiful harvest. The studio’s signature lies in its ability to produce such intricate designs through unique cutting techniques and to achieve brilliant transparency and shine through expert polishing.

The Kome-tsunagi cut design

Mrs. Chisato Kumakura, the second-generation leader of Hanashyo and daughter of Mr. Ryuichi Kumakura, continues to share her father’s artistic vision both within Japan and internationally. Standing between artisans and customers, she has a unique perspective on artisan well-being and the role of sensibility in craftsmanship. I had the privilege of hearing her thoughts on both.

1.3. The Well-being of Edo Kiriko Artisans – Three Key Elements

From the interview with the company president, three key elements emerged as central to the well-being of Edo Kiriko artisans:

1. Artisans enter a state of flow (Engagement) by sensing subtle presences through their five senses.

→ In this article, I refer to this phenomenon as “Kansei-based Well-being through Perception.”

2. Their sensitivity in expressing their own “soul” leads to continuous creative output.

→ This relates to the “Let’s Try” factor and Dr. Martin Seligman’s PERMA theory, specifically the “Accomplishment” dimension.

→ I describe this as “Kansei-based Well-being through Expression.”

→ To create works infused with good energy, being in a good physical and mental state—that is, maintaining one’s health—is essential.

3. Observational and imaginative abilities that allow artisans to “converse” with their works.

→ This suggests the “Meaning” and “Relationships” dimensions in the PERMA theory.

Let’s take a closer look at each of these three elements, incorporating insights from the interview.

\ Welcome to Hanashyo Nihonbashi Store! /

As you step inside, you’re greeted by dazzling, one-of-a-kind Edo Kiriko pieces.

Not only the traditional hues of lapis lazuli, crimson, white, and black, but also colours reminiscent of seasonal scenes—fresh green like early summer foliage, summer blue evoking clear oceans and skies, soft orange, and pale grape tones. Surrounded by these vibrant colours, you’re instantly lifted into a brighter mood.

(The warm glow of the Edo Kiriko lampshades was deeply soothing.)

The following passages include direct quotes from Mrs. Chisato Kumakura (“ … ”) and comments from Miyaji (“< … >”).

2. The Kansei-Based Well-being of Edo Kiriko Artisans – Three Key Elements

2.1 What Does the Artisan’s Flow State Look Like?

(1) Entering a “Flow State” During Edo Kiriko Crafting

“Since we also run Edo Kiriko classes, members of the general public have opportunities to try it. And when people are engaged in Edo Kiriko, they stop thinking about unnecessary things—the only sounds are those of the machine and the glass resonating with each other. It feels like Zen training. They say they reach a state of mu (emptiness), and it’s incredibly pleasant.

Some people come after work in the evening, and it seems to refresh them. I think the artisans probably experience that feeling every day. I’d love to measure their brainwaves—maybe they’re releasing happiness hormones like serotonin… Of course, there’s the joy of making something with your hands, but I believe something different is happening neurologically.”

According to research by Kaimal et al. (2016), creating art reduces the level of cortisol, the stress hormone, in the body. If I were to actually measure brain activity or heart rate, I might find differences between artisans and people who haven’t experienced Kiriko crafting. (If anyone reading this is involved in such research, I’d love to collaborate!)

(2) Physical and Mental Well-being Through Regulated Breathing

“Since I work in sales, my breathing tends to be shallow—maybe it’s a weird way to put it, but I always feel a sense of urgency about needing to sell something.

But the artisans who do the cutting here have a steady breathing rhythm… I feel like it might help regulate their autonomic nervous system.”

(3) Entering Flow by Sharpening the Five Senses

“Apparently, you can tell from the sound whether the cut is going well or not. My father used to work here with the staff, and they would all listen to each other’s cutting sounds. And they’d notice—‘this doesn’t sound like Dad’s.’

Rather than being told what to do, they sense things through subtle cues. In the beginning, their cutting sounds lack lightness.”

<So their five senses are highly tuned.>

“Also, during the school sessions, which last about two hours, people don’t touch digital devices. That kind of digital detox might also be helpful.”

“I think artisans spend more of their daily lives attuned to subtle signs, using their five senses and sensibility, compared to the general public—and maybe that’s why they find it so enjoyable.”

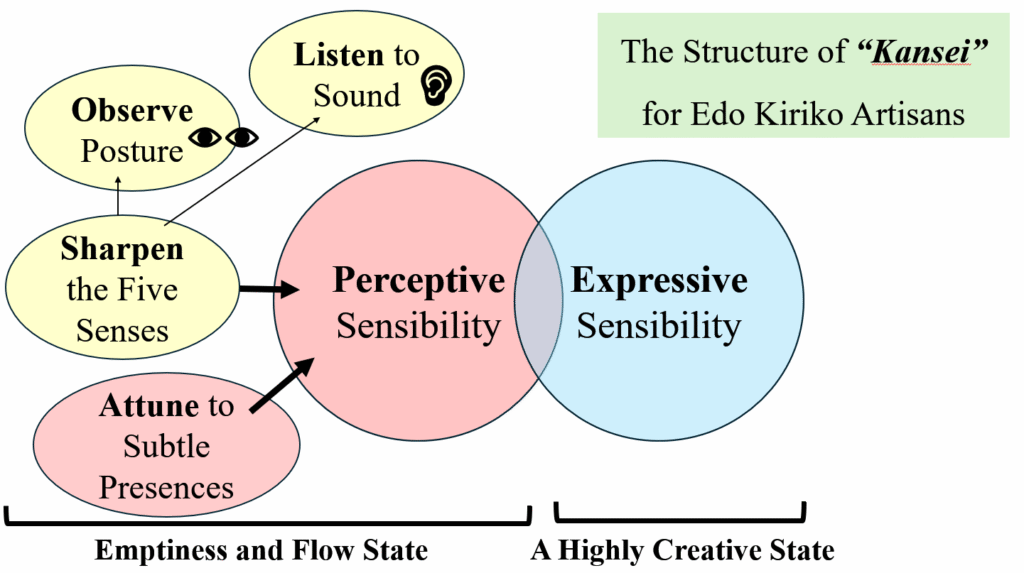

A Diagram of the “Sensory Structure” of Edo Kiriko Artisans That Suggests the Potential of Kansei-based Well-being (Miyaji, 2025)

I believe that there is a strong affinity between kansei (sensibility) and well-being.

According to Nagashima (2014, p.109), kansei consists of two components: the sensibility to perceive and the sensibility to express. Through Mrs. Chisato Kumakura’s reflections, it became evident that these two modes of kansei are closely linked to states such as mu (emptiness), flow, and even heightened creativity.

This suggests a clear connection between the dual aspects of kansei—“perceiving” and “expressing”—and one’s positive state of being. Based on this, I have coined the term Kansei-based Well-being to describe the phenomenon in which Kansei experiences lead to enhanced well-being.

I believe there is a growing need for deeper discussions about the significance of this concept across diverse contexts.

< Sensing Subtle Cues – A Japanese Sensibility >

The ability to sense subtle cues—kehai—may be something that aligns closely with the Japanese sensibility, which is often described as valuing harmony and cooperation. The phrase “reading the air” (kuuki wo yomu) tends to evoke the idea of social pressure and emotional strain, and thus doesn’t always carry a positive connotation. However, in the world of artisans, the ability to intuitively sense one another’s presence—without the need for words—may in fact be a vital and instinctive skill.

This leads us to a new question: to what extent is this kind of kehai-sensitive sensibility valued in other fields of craftsmanship, or in artisan cultures outside of Japan?

(4) The Bodily Transmission of Cutting Techniques

In the world of artisanship, the ability to sense is also essential when it comes to passing down skills.

<So even technical skills are passed on this way…>

“Exactly. It’s about listening to the sound—hearing whether something sounds off, or whether the speed matches. If something feels off, it means there’s a mismatch in some aspect. That’s how it works.”

<It’s like playing music together.>

“It really is. You watch the speed and the posture. You’re told: ‘Figure out what you’re missing by watching closely.’

And when someone’s working right next to you, suddenly you’re able to work much faster. It’s fascinating. That’s when you realize—this is what it means to learn with your body.”

So far, I have explored the flow experiences of Edo Kiriko artisans. Through careful observation of the second-generation artisan’s cutting posture and attentive listening to the sound of the glass being cut, I have come to understand the importance of sharpening the five senses and the ability to sense subtle presence.

The fact that many people join evening classes after work in search of a state of mu or flow further highlights just how comforting and appealing this state can be.

Now, let’s turn to the other dimension of kansei—the sensibility to express.

2.2. The Relationship Between High Creativity and Well-being

<The artisans are constantly engaged in self-expression, aren’t they?>

“Yes, that’s right. And when it comes to expressing your inner self through design, it’s actually quite rare to have opportunities to do so. Being able to express oneself like that—I think that’s a form of happiness. At least, that’s my guess.”

<There’s also research showing that highly creative individuals tend to be happier…>

Chūbuki-style Large Green Bowl

Crafted by Second-generation Artisan Ryuichi Kumakura, from the Hanashyo website

When it comes to the expressive aspect of kansei, it seems necessary to explore more deeply how high levels of creativity specifically contribute to the artisan’s sense of well-being.

When asked about artisan well-being based on the PERMA theory, Mrs. Chisato Kumakura noted that Accomplishment is particularly tangible in their field, since the completion of a piece yields a clear, visible outcome—making it easier for artisans to recognize and feel a sense of achievement.

Keyes and colleagues have shown that participation in creative activities significantly enhances well-being by providing meaningful opportunities for expression and achievement. This is exactly what appears to be happening at the Hanashyo workshop: a space for creative expression and accomplishment that contributes greatly to the artisans’ happiness.

(1) Artworks Infused with the Artisan’s Soul Bring Happiness to Others

“When I observe the artisans, they don’t seem to be driven by a strong sense of duty or mission. It feels more like they’re simply enjoying the comfort of being fully present in the moment. And because they’re doing what they truly want to do, that sense of fulfillment brings them happiness.”

As mentioned earlier, creative, artistic and craft activities enhance self-expression and a sense of accomplishment. Furthermore, research shows that engaging in such activities also boosts life satisfaction, a sense that life is worthwhile, and overall happiness (Keyes et al., 2024).

The way the president described the artisans gave the impression that they aren’t bound by concepts like “purpose” or “goals.” Instead, they immerse themselves in the here and now, passionately engaging in what they love and feeling fulfilled. This attitude seems to lead naturally to self-expression and a sense of achievement, strongly aligning with existing research findings.

“The artisans don’t really say they’re creating for someone else or for the customers. They just make what they want to make, and in doing so, they pour their soul into the work. If someone receives it and has a good experience, that’s great. But it’s not about marketing or figuring out what will sell—it’s nothing like that.”

What exactly does it mean to “infuse a soul” into a piece of work? If the artisan’s state of being is reflected in the work, then clearly the artisan’s health is fundamental. The president shared her thoughts on this point as well.

(2) An Artisan’s “Health” is Reflected in Their Work

“Putting your soul into your work is the most important thing. It’s not really about doing it for someone else. I mean, if it ends up benefitting someone, that’s wonderful—but it’s not the primary goal. That’s probably why they don’t get emotionally drained.

When it’s for yourself, you don’t get worn out. I used to think everyone was being selfish, but maybe that’s actually a good thing.

If you are healthy, then what you create will also be ‘healthy,’ and the person who receives it will feel that good energy. That’s why I believe I need to stay healthy.”

This message deeply resonates and seems universally relevant—no matter what profession or role one holds.

(3) Her Father’s Presence—A Source of Overflowing Energy

“My father (the second-generation artisan) wakes up every morning excited, thinking, ‘What should I make today?’ Creating is part of his daily life—and I think it brings him joy. That really struck me.

He hasn’t changed at all since I was a child. And because my father is that kind of person, the staff also enjoy being with him in the morning. There’s a real sense of energy coming from the person doing the creating.”

Mr. Ryuichi Kumakura, Second-Generation Artisan (from the Hanashyo Website)

The presence of her father, radiating positive energy, warms the atmosphere of the workplace and fills the studio with vitality. In this energetic workshop, artisans create works infused with their soul. It is Mrs. Chisato Kumakura who conveys the beauty and spirit of these creations to customers. Having previously worked as a junior high school teacher and in sales, her unique approach to presenting the pieces centres around one key concept: “dialogue with the work.”

Mr. Ryuichi Kumakura, the second-generation artisan, was awarded the Order of the Rising Sun, Gold and Silver Rays in the Spring 2024 Honours.

2.3. “Dialogue with the Work” Born from Past Experiences

“I once went through an illness. At the time, I was constantly organizing events ‘for the customers, for the customers,’ and eventually I became emotionally worn out.

But when I shifted my thinking toward how to communicate the essence of a piece, how to convey it to someone who genuinely wants to connect with it—that made all the difference.”

<So you began to focus more on the people who are truly drawn to the works.>

“Yes. I personally learned that what’s important is how we engage with people who genuinely love the work.”

(1) Sensing the Sensibility of a Piece Without Words

“There’s something about a space’s aura… it’s joyful to be near people who are having a positive experience. And when you’re beside someone giving off a negative aura, it’s exhausting.

I believe that we humans live by sensing these subtle presences more than we realise, and I wish we’d place more value on that.”

“When I explain the work too directly—like saying ‘this is this, and that’s that’—it somehow strips away the sensibility the piece carries.”

“Sometimes I guide international guests through the workshop, and they’ll say, ‘I just want to look. You don’t need to explain anything.’ And that made me realize—words aren’t necessary.”

“It’s more about sensing the person’s atmosphere and vibe. The more you explain, the more it starts to drift away from how they actually feel.”

Chisato places great importance on the atmosphere and presence of both the space and the work itself. Through her stories, I too gained a new perspective—reminding me to hone my powers of observation and imagination when appreciating artworks.

(2) Dialoguing with the Work to Convey Its Essence

<Going back a bit—when you communicate the work to a customer, what is the role of your personal ‘dialogue’ with the piece?>

“Well… it’s a bit embarrassing to say, but sometimes I’ll look at a piece and think, ‘Wow, this part is really shining today,’ or ‘I wonder what my father had in mind when he made this.’

When he visited the National Palace Museum in Taiwan recently, my father said, ‘I’m going to have a conversation with the artisans from back then—to feel what they felt as they made these works.’

I was struck by that way of seeing. Like, ‘This must be the part they really wanted to emphasize,’ or ‘They were trying something new with this line.’

Sometimes the style changes suddenly, and when it does, I think, ‘Ah, this must be a transitional phase.’ I often ask questions at the studio:

‘This piece caught my eye—what were you thinking when you made it?’ and they tell me.

I probably couldn’t have done any of this if I’d only worked in business. It all started to change when I entered graduate school to study cultural anthropology and had those deep dialogues with my professors.”

Mrs. Kumakura is currently pursuing a PhD in cultural anthropology at the Tokyo University of Science.

(This marks the end of the interview.)

Mrs. Chisato Kumakura is now actively working to promote the beauty of Edo Kiriko around the world, including in Paris, London, and the Netherlands. Though she radiates warmth and cheer, it’s clear that her past experiences and current studies in the doctoral program have shaped her deeply reflective approach, placing great importance on “dialogue with the work.” Her presence alone was energising and inspiring.

The Kome-tsunagi (linked rice grain) wine glasses crafted by the second-generation artisan, Mr. Ryuichi Kumakura, were also selected as gifts for the 2008 Toyako G8 Summit.

I sincerely wish Hanashyo continued success and growth.

3. Conclusion

Through my conversation with Mrs. Chisato Kumakura, I came to see that the act of creating Kiriko glass itself brings a sense of calm and induces a flow state—largely because it requires artisans to sense subtle cues through their five senses, such as the rhythm of their breathing and the sound of the cutting process. This atmosphere plays a crucial role.

In addition, the dual nature of kansei—the ability to perceive and to express what one has felt—was clearly reflected in the story of her father, revealing how the joy of expression is deeply connected to an artisan’s sense of well-being.

Finally, Mrs. Kumakura shared her own view of happiness: as the company president, her role in conveying the spirit of Hanashyo’s Edo Kiriko lies in dialoguing with the work, or in other words, contemplating what the artisan was feeling and thinking when creating the piece.

< From the Perspective of Japanese Well-being >

Looking back at the interview through the lens of Japanese-style well-being, the practices highlighted in this report—such as the artisan’s breathing, sensitivity to sound, shared sense of presence, and dialogue with the work—strongly reflect the sensibility of harmony.

This form of kansei-based well-being offers important insight into the unique nature of happiness as understood within Japanese culture and sensibility. It may serve as a valuable clue in understanding how well-being is experienced and cultivated in a culturally specific context.

Finally, the importance of uncovering the mechanisms by which craft and art relate to well-being has been noted in the work of Keyes et al. (2024). This report, grounded in firsthand accounts from Japan, may represent a meaningful step toward contributing new perspectives to this growing field of research.

4. Looking Ahead

Through this exploration of the sensory structure of Edo Kiriko artisans, I have gained a valuable starting point for considering the relationship between artisans’ happiness and well-being. This study can be positioned as a preliminary investigation prior to future interviews with artisans themselves.

< Diverse Sensibilities and Well-being >

If kansei (sensibility) plays such an important role in the world of craftsmanship, a new question arises: How do artisans—or perhaps more inclusively, creators—with sensory impairments perceive subtle presence (kehai) and express it through their work?

This interview has sparked a desire to explore a world where people with diverse ways of sensing and expressing engage in craftsmanship. I hope to look beyond a single standard of sensibility and instead open up the question: What does a truly inclusive and happy world look like, one that embraces diverse forms of perception and expression?

Moving forward, I would like to continue exploring the potential of handwork as a space where diverse sensibilities intersect and where well-being can be fostered for all.

─────── ⸙ ───────

Dear Mrs. Chisato,

Thank you so much for taking the time to speak with me during my visit. I truly appreciate your generosity and the valuable insights you shared. I also enjoyed learning about your favourite spots in Nihonbashi—it allowed me to feel the unique charm of the area even more.

I’m very much looking forward to the opportunity to speak directly with the artisans in the future!

Photo: Mrs. Chisato and the author at Hanashyo, Nihonbashi.

References

Clark, F. (2024). Making arts and crafts improves your mental health as much as having a job, scientists find. CNN Health.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990). Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience. Harper & Row.

Kaimal, G., Ray, K., & Muniz, J. (2016). Reduction of Cortisol Levels and Participants’ Responses Following Art Making. Art Therapy, 33(2), 74–80. doi:10.1080/07421656.2016.1166832

Keyes, H., et al. (2024). Creating arts and crafting positively predicts subjective wellbeing. Frontiers in Public Health, 12, 1417997. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2024.1417997

Cabinet Office, Government of Japan. (2022). Public Opinion Survey on Social Awareness (December 2021 Survey): 2. Perceptions of the Current State of Society (3) Pride in Japan. Retrieved June 24, 2025.

Cabinet Office, Government of Japan. (2022). Public Opinion Survey on National Life (September 2021 Survey): 2. Regarding Future Life (3) Mental Fulfillment or Material Wealth. Retrieved June 24, 2025.

Nagashima, T. (2014). Sensible Thinking: Bridging Science and Humanities. Tokai University Press.